The Fourier transform: pt.1

- 6 minsIntroduction

If there’s one thing the internet is full of (except for cats) it’s tutorials about the Fourier transform. Some of these are really well done, so why should anyone bother to write more blog posts about the topic?

In my case, the answer is quite selfish: I’m currently studying DSP into depth via Sanjit Mitra’s great book “Digital signal processing: a computer-based approach”, and I want some vehicle to test my deeper understanding of the underlying concepts, beyond solving the (many) exercises in the book. What better way to do so than by trying to mediate my understanding to an another reader?

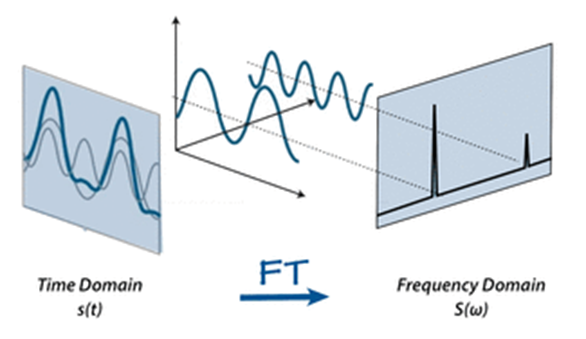

The basics

Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (DTFT)

Let’s start with some definitions. Let x[n] be some sequence (if x[n] is finite- we extend it infinitely in each direction by zero-padding). The Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (DTFT) of a discrete-time signal x[n] is given by the following formula:

Where:

- We say $x[n]\overset{\text{FT}}{\leftrightarrow}X(e^{j\omega})$ constitute a Fourier transform pair.

- $\omega$ is the angular frequency in radians per sample. Notice $X(e^{j\omega})=X(e^{j(\omega+2\pi)})$ meaning the DTFT is $2\pi$-periodic in $\omega$, so we can take any $2\pi$ wide interval of choice to uniquely describe $X(e^{j\omega})$.

Inverse Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (IDTFT)

The Inverse Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (IDTFT) allows us to recover the original signal x[n] from its DTFT $X(e^{j\omega})$ and is given by:

Where:

- x[n] is the original discrete-time signal.

- The integral is taken over the specified frequency range, which can also be defined simply as $R = [\omega_0,\omega_0+2\pi]$, making the integral $\int_{\omega\in R}$.

What’s that integral about? Hopefully we’ll have a simpler interpretation of it later.

A simple (yet illuminating) problem

The following problem from Mitra’s book was an eye-opener for me regarding the IDTFT, and thus felt worth sharing.

The problem is as such: let $X(e^{jw})$ denote the DTFT of a sequence x[n]. Evaluate $\int_{-\pi}^{\pi} X(e^{j\omega})d\omega$.

A simple solution to this problem, which makes use of the previous definitions, is

But can we perhaps choose to look at the problem differently, and make some sense of it in a different, more meaningful way? Let’s try as an initial step to “open up” each $X(e^{j\omega})$ by representing it via the DTFT operation over x[n]

Now let’s make some sense of that integral in two different ways, the first ‘naive’ (with zero-initial knowledge) and the second informed (using Fourier transform properties).

The naive way

The indefinite integral of $( e^{-j \omega n} )$ with respect to $\omega$ is:

Applying the limits from $( -\pi )$ to $( \pi )$:

Where I[n] is a sequence because we suppose n is an integer (remember the summation over n in the DTFT calculation).

This can be simplified using Euler’s formula:

yielding

We notice that this expression is equal to zero for all non-zero integer values of n, and is undefined for $n=0$. We could compute the limit $\lim_{x \to 0}I[n]$, but let’s instead go back to the original integral formulation:

Finally we have

This sequence looks familiar: it is none other than $2\pi\delta[n]$, where

. The resulting sequence is so basic- could there have there an easier way to compute it?

The informed way

Fourier analysis is generally done by utilizing certain mathematical properties of Fourier transforms, together with some well-known pairs of sequences/functions under such transforms. The most basic such pair is $\delta[n]\overset{\text{FT}}{\leftrightarrow}1$, which is obvious because

This can easily be verified via the convolution theorem, which states

Where $x[n]\circledast h[n]=\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} x[k]h[n-k]$ is the convolution operator.

In the case of h[n] = $\delta[n]$, we know it is the identity element for the convolution operator, meaning $x[n]\circledast \delta[n]=x[n]$, and it must thus translate to the identity of the multiplication operator in the frequency domain, meaning $H(e^{jw})=1$.

Note: we can prove the same result by using the modulation theorem

where we set $H(e^{jw})=2\pi\delta(e^{jw})$, thus yielding h[n]=1.

The duality theorem

A useful theorem for Fourier transforms defined over the same time/frequency domain (be it continuous or discreet) is the duality theorem, whereby

meaning we can interpret the frequency-domain representation $X(e^{jw})$ as a time-domain representation and then take the Fourier transform of this, resulting in a scaled and time-reversed version of the time-domain representation (exercise for the reader: what would taking 4 consecutive DTFTs of an initial sequence x[n] result in?). The convolution and modulation theorems also express the notion of duality, in the sense that they are equivalent operators in the two domains. While the DTFT is a bit ‘problematic’ in this scenario (in the sense that the time-domain is discrete whereas the frequency domain is continuous), we can bypass this by using a little trick: let’s define

and use it to prove the duality theorem for the DTFT.

Finally, we can use the FT pair $\delta[n]\overset{\text{FT}}{\leftrightarrow}1$ to solve the mystery integral

giving us the same result as previously.

Going back now to the original problem we have once more

What have we learned so far? That we can interpret the integral $\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}e^{-j\omega n} d\omega$ as the DTFT operator over the frequency-domain representation $X(e^{jw})=1$, thus yielding the scaled original time-domain sequence $2\pi\delta[n]$. But can we learn something more about the IDTFT using this toy example?

The time-shift theorem

Another theorem relating to Fourier transforms which will prove useful for this purpose is the time-shift theorem

which intuitively establishes a relationship between a time-shift in the time-domain and a phase-shift in the frequency domain. We can use this theorem to verify that

Meaning we now have a general interpretation of the IDTFT as a time-shifted version of the original problem

Conclusion

Mitra’s seemingly innocent problem emphasizes the duality between the time and frequency-domain representations of a signal, which is an inherent property of the Fourier transform. Under this interpretation- the IDTFT becomes nothing more than a phase-shifted summation equivalent to “plucking” out the relevant index from the time-domain representation x[n] via a time-shifted unit sequence.

That’s it for now!